by David Bacon

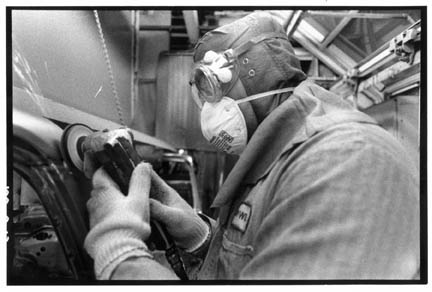

People have spent their lives in the NUMMI plant in Fremont, probably more time with the compressed-air tools at their workstations than with their families at home. The plant is like a city, thousands of jobs and thousands of people working in a complicated dance where each one's contribution makes possible that of the next person down the line. And like a city, it supports the people who work in it.

A NUMMI job brings the paycheck that pays the mortgage and the (now astronomical) tuition for kids in college. A NUMMI job makes possible the friendships that grow over years laboring in the same workplace. Working at NUMMI means being part of the union, with all the frustrations and infighting, but also the ability to pull together to get the contract that makes an industrial job bearable, and ensures that a kid's visit to a doctor or dentist doesn't bottom out the family bank account.

General Motors used to run this plant by itself, back in the '60s and '70s, when it was GM Fremont. It was a feisty plant with a feisty union, and a linchpin for years in the movement to stop concessions in union bargaining. When GM closed the plant the first time, in the early '80s, many thought it was revenge. Afterwards, autoworkers from Fremont became migrants. Many lived a lonely existence in motels in Oklahoma City or Texas, trying to hold onto seniority in a union auto job, sending money back home to families in California. Others lost their homes, and worse. In the wave of plant closures of the early 1980s, the Department of Commerce even kept a statistic of how many people committed suicide for every thousand who lost jobs when their plant shut down. No one in Washington has the courage to face that number anymore.

No comments:

Post a Comment