The road to Fort Ashby, West Virginia, runs through Mineral County, an area of freezing grey farmland and barrack-style bungalows, where the sign outside the bar - "Hunters welcome" - has an unnerving effect on the passing non-hunter. In Cindy's coffee shop, customers speculate on the whereabouts of a lost cow and tell a weird Republican joke about the noise a chicken makes when its head is cut off: "Barack-Obama!, Barack-Obama!" Lynndie England has lived in Fort Ashby since she was two, but when she appears, suddenly, in the car park, her outline is crooked with self-consciousness. She grew her hair for a while, but people recognised her anyway, so she cut it short again.

The road to Fort Ashby, West Virginia, runs through Mineral County, an area of freezing grey farmland and barrack-style bungalows, where the sign outside the bar - "Hunters welcome" - has an unnerving effect on the passing non-hunter. In Cindy's coffee shop, customers speculate on the whereabouts of a lost cow and tell a weird Republican joke about the noise a chicken makes when its head is cut off: "Barack-Obama!, Barack-Obama!" Lynndie England has lived in Fort Ashby since she was two, but when she appears, suddenly, in the car park, her outline is crooked with self-consciousness. She grew her hair for a while, but people recognised her anyway, so she cut it short again.

The last time journalists came to Fort Ashby in any number, they upset residents by portraying it as "a giant trailer park". There are two bars, two banks, a fire station, a school and a bookshop - the woman who runs the latter says, "I've no sympathy for what she did, but people behave differently in war than they do in their chairs at home, watching it on TV."

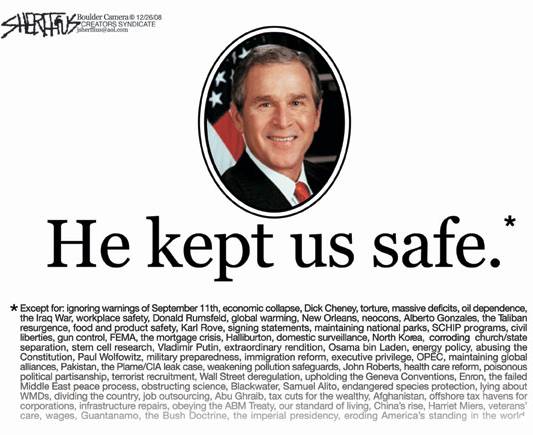

It is almost two years since England returned home after serving half of a three-year sentence for maltreating prisoners at Abu Ghraib. In mid-December, a report by the Senate armed services committee concluded that, contrary to the US government's assertion that a few "bad apples" were to blame for abuses at the prison, responsibility ultimately lay with Bush officials, including the defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld, for policies that "conveyed the message that physical pressures and degradation were appropriate treatment for detainees". (A spokesman for Rumsfeld rejected the findings as "unfounded allegations against those who have served our nation".

Whatever the official findings, the face of the scandal will always be that of the then 21-year-old Private Lynndie England. She wasn't the only woman soldier in the photographs - Sabrina Harman and Megan Ambuhl were both court martialled for their roles - but England was the most arresting looking, like a 14-year-old boy who shouldn't have been there in the first place. Her legal defence, that she was unduly influenced by Specialist Charles Graner, the father of her child and the only soldier still serving time for abuses at Abu Ghraib, was compounded outside the courtroom by assumptions about her background; that she came from a place where people didn't know better.

England is now 26 and spends her days looking for a job, caring for her son and trying to avoid running into people she went to high school with. In the frigid air outside the coffee shop, she talks to her lawyer, Roy, and looks away when I approach. Roy is a Gulf war veteran and assistant county prosecutor who, since her release, has acted as England's chaperone and press agent. Roy suggests we drive in convoy to the bar where hunters are welcome and where the interview will proceed.

After her release, England moved back in with her parents. Her sister, Jessie, lives with her family in the trailer opposite. England and her four-year-old son, Carter, sleep in a single bed customised from the bunk beds she and Jessie slept on when growing up.

"Everybody always wants to know about the trailers," Roy says. Although it's midday, the windows in the bar are shuttered and in a couple of hours the patrons will be drunk enough to come over to England and start offering their opinions. Roy shrugs: "For the most part, it's just low-income housing."

"Well, you know what?" England says. "In New York - I've never been to New York, but I've heard people say - there's apartments there where people pay $1,500 a month for something smaller than a trailer. We only pay $200. And they look down on us. It's like, you're stupid."

Her attempts to find a job have so far been unsuccessful. Most of the fast-food joints in the area won't employ felons, and when she goes for an administrative job, she makes it to the second interview before word gets back that the staff would feel uncomfortable working with her.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jan/03/abu-ghraib-lynndie-england-interview

Honah Lee-Puff the Magic Dragon held a news conference today to denounce the musical massacre of the beloved children's song "Puff The Magic Dragon" by conservative musician Paul Shanklin and the subsequent distribution of the mutilated song by RNC leadership hopeful Chip Saltsman and talkshow host Rush Limbaugh. Shanklin had already incensed the black community and most of America with his rendition of "Barack the Magic Negro", a song which was distributed to all Republican National Convention members by Saltsman and played on Limbaugh's show.

Honah Lee-Puff the Magic Dragon held a news conference today to denounce the musical massacre of the beloved children's song "Puff The Magic Dragon" by conservative musician Paul Shanklin and the subsequent distribution of the mutilated song by RNC leadership hopeful Chip Saltsman and talkshow host Rush Limbaugh. Shanklin had already incensed the black community and most of America with his rendition of "Barack the Magic Negro", a song which was distributed to all Republican National Convention members by Saltsman and played on Limbaugh's show.

But they never did. Eight years later, the barricades remain. It was a phony issue, of course — just another stick with which to beat Bill Clinton, who closed the road at the insistence of the Secret Service. In an interview with PBS a month after Sept. 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney stated the obvious: "Pennsylvania Avenue ought to stay closed because, as a fact, if somebody were to detonate a truck bomb in front of the White House, it would probably level the White House, and that is unacceptable."

But they never did. Eight years later, the barricades remain. It was a phony issue, of course — just another stick with which to beat Bill Clinton, who closed the road at the insistence of the Secret Service. In an interview with PBS a month after Sept. 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney stated the obvious: "Pennsylvania Avenue ought to stay closed because, as a fact, if somebody were to detonate a truck bomb in front of the White House, it would probably level the White House, and that is unacceptable."

![jdsalinger.jpg [Salinger in 1951, the year Catcher in the Rye was published]](http://www.commondreams.org/files/article_images/jdsalinger.jpg) There are apparently no plans for J.D. Salinger, the literary leviathan whose truncated canon most famously includes

There are apparently no plans for J.D. Salinger, the literary leviathan whose truncated canon most famously includes

The road to Fort Ashby, West Virginia, runs through Mineral County, an area of freezing grey farmland and barrack-style bungalows, where the sign outside the bar - "Hunters welcome" - has an unnerving effect on the passing non-hunter. In Cindy's coffee shop, customers speculate on the whereabouts of a lost cow and tell a weird Republican joke about the noise a chicken makes when its head is cut off: "Barack-Obama!, Barack-Obama!" Lynndie England has lived in Fort Ashby since she was two, but when she appears, suddenly, in the car park, her outline is crooked with self-consciousness. She grew her hair for a while, but people recognised her anyway, so she cut it short again.

The road to Fort Ashby, West Virginia, runs through Mineral County, an area of freezing grey farmland and barrack-style bungalows, where the sign outside the bar - "Hunters welcome" - has an unnerving effect on the passing non-hunter. In Cindy's coffee shop, customers speculate on the whereabouts of a lost cow and tell a weird Republican joke about the noise a chicken makes when its head is cut off: "Barack-Obama!, Barack-Obama!" Lynndie England has lived in Fort Ashby since she was two, but when she appears, suddenly, in the car park, her outline is crooked with self-consciousness. She grew her hair for a while, but people recognised her anyway, so she cut it short again.