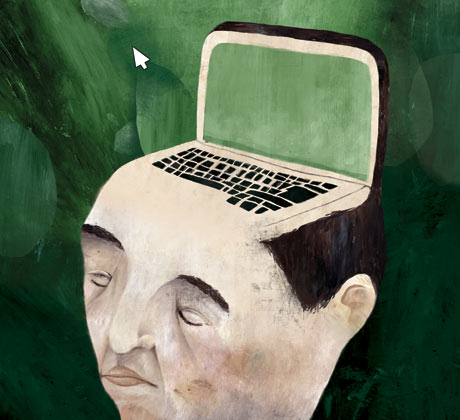

The energy needed to obtain information when required has diminished to almost nothing, so why bother learning stuff?

A couple of years ago, a neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin noticed what seemed to be an unexpected byproduct of the digital age: a third of the under-30s he questioned didn't know their own phone numbers. They were worse than their elders, too, at remembering relatives' birthdays. It's tempting to wonder what else they didn't know: the formula to convert feet to metres? The prime minister of France? Why bother, after all, when the energy needed to obtain the information when required, from a hard drive or the internet, had diminished to almost nothing? "The line between where my memory leaves off and Google picks up is getting blurrier by the second," one Wired magazine writer observed. "Almost without noticing it, we've outsourced important peripheral brain functions to the silicon around us." Me, too. Until recently, I had to check my mobile to remember my home phone number. (Apologies to readers under 30 who've probably never heard of a "home phone". Why not look it up on the web?)

A couple of years ago, a neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin noticed what seemed to be an unexpected byproduct of the digital age: a third of the under-30s he questioned didn't know their own phone numbers. They were worse than their elders, too, at remembering relatives' birthdays. It's tempting to wonder what else they didn't know: the formula to convert feet to metres? The prime minister of France? Why bother, after all, when the energy needed to obtain the information when required, from a hard drive or the internet, had diminished to almost nothing? "The line between where my memory leaves off and Google picks up is getting blurrier by the second," one Wired magazine writer observed. "Almost without noticing it, we've outsourced important peripheral brain functions to the silicon around us." Me, too. Until recently, I had to check my mobile to remember my home phone number. (Apologies to readers under 30 who've probably never heard of a "home phone". Why not look it up on the web?)I've previously sung the praises of organisational guru David Allen's insight that getting stuff out of your head is a path to mental calm. Everyday stress, he theorises, results from your mind trying not to forget everything that's on your plate. So keep your to-dos in a "trusted system" – a notebook, a computer file – and you will gradually relax, knowing there's no chance of anything slipping through the cracks. But must relaxation come at the cost of an atrophying brain? Besides, not every form of outboard storage is equally trustable. When a friend recently revealed she had stored weeks of work only online, using Google Docs, my involuntary response bore a strong resemblance to Edvard Munch's The Scream. I know Google won't lose her work, whereas my laptop, where I keep similar things, may well get stolen. But my anxiety wasn't based on the probabilities. It felt more existential than that.

The real point here, I think, isn't primarily about technology. Rather, it's the way we're invested in the things in the world that we think of as ours. I'd be nervous giving Google sole stewardship of something I was writing, because somehow it's a bit of me. Maybe the aversion I feel towards Twitter is that I don't want part of me in yet another location online. I'd feel scattered, overextended. (It's a good excuse, anyway.) There's a connection here to the cult of "decluttering". Your stuff and yourself are linked: the former contains part of the latter. Perhaps that's why people who radically streamline their possessions report feeling physically lighter.

I'm not suggesting trying to reverse the technological tide, nor giving all your belongings away. But it's worth thinking hard about the forms in which we store bits of ourselves in the outside world; it may affect us, emotionally, more than we realise.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/aug/29/change-your-life-learning

No comments:

Post a Comment